Prison censorship is the number one First Amendment violation in America. Prison censorship is intimately tied to the legacy of slavery, and despite the bounty of research about how access to books and libraries reduces recidivism, every day, those on the inside and outside find that the rules about which books are allowed in these institutions change without warning.

Last year, in honor of Prison Censorship Week, we ran three powerful pieces from individuals experiencing incarceration about where and how access to books and reading has been crucial to them. With Banned Books Week around the corner–October 6-12–and Prison Banned Books Week after that–October 19-25–it’s beyond time to talk with experts in prison book censorship to learn what’s going on right now and where advocates for intellectual freedom can support the fight for’ First Amendment Rights to those experiencing imprisonment. It is especially important to remember that, despite a wave of anti-book ban laws penned in several states across the country, most of those do not provide any protections to incarcerated individuals. Only one state addressed prison censorship in its suite of anti-book ban laws, and that was California with Assembly Bill 1986.

Michelle Dillon is one of the most knowledgeable and engaged individuals on the topic of prison censorship, and I’m honored to have her share insights and action steps related to it this week.

***

Each week, in cramped church basements and community rooms across the country, dozens of groups of volunteers come together to provide books to some of the most underserved readers in the United States: people who are experiencing incarceration. These volunteer organizations, like Books to Prisoners Seattle (BTP)—with which I have volunteered since 2012—collectively receive thousands of letters each year from people who are incarcerated in jails, prisons, and immigration detention centers. The people who send the letters request self-help books, books about entrepreneurship, history books, pulp science fiction novels, classic Russian literature, and, sometimes, simply, “a really good book to help pass the time in here.”

In response to these letters, volunteers pore through shelves of donated books. They deliberate over whether the letter writer who asked for more books like Patrick Rothfuss’ The Name of the Wind will be satisfied with a book by Brandon Sanderson. They consider whether there are any light thesauruses on the shelf to accompany a request for a dictionary, and whether the receiving prison will allow a package of a certain weight or will allow a certain number of books inside the package (some prison systems limit the volume of books, like the Alabama DOC, which caps the number of books that a person can receive from all sources combined to two books per month). Once chosen, books are wrapped, labeled, stamped, and mailed to the eagerly waiting reader, who receives the books at no cost. In thank you letters, readers tell us that books are passed around their unit, to be read and treasured in turn. Patrons speak of unquantifiable benefits provided in a system where outlets for books are scarce and on-site libraries are frequently closed, hard to access, or even non-existent.

|

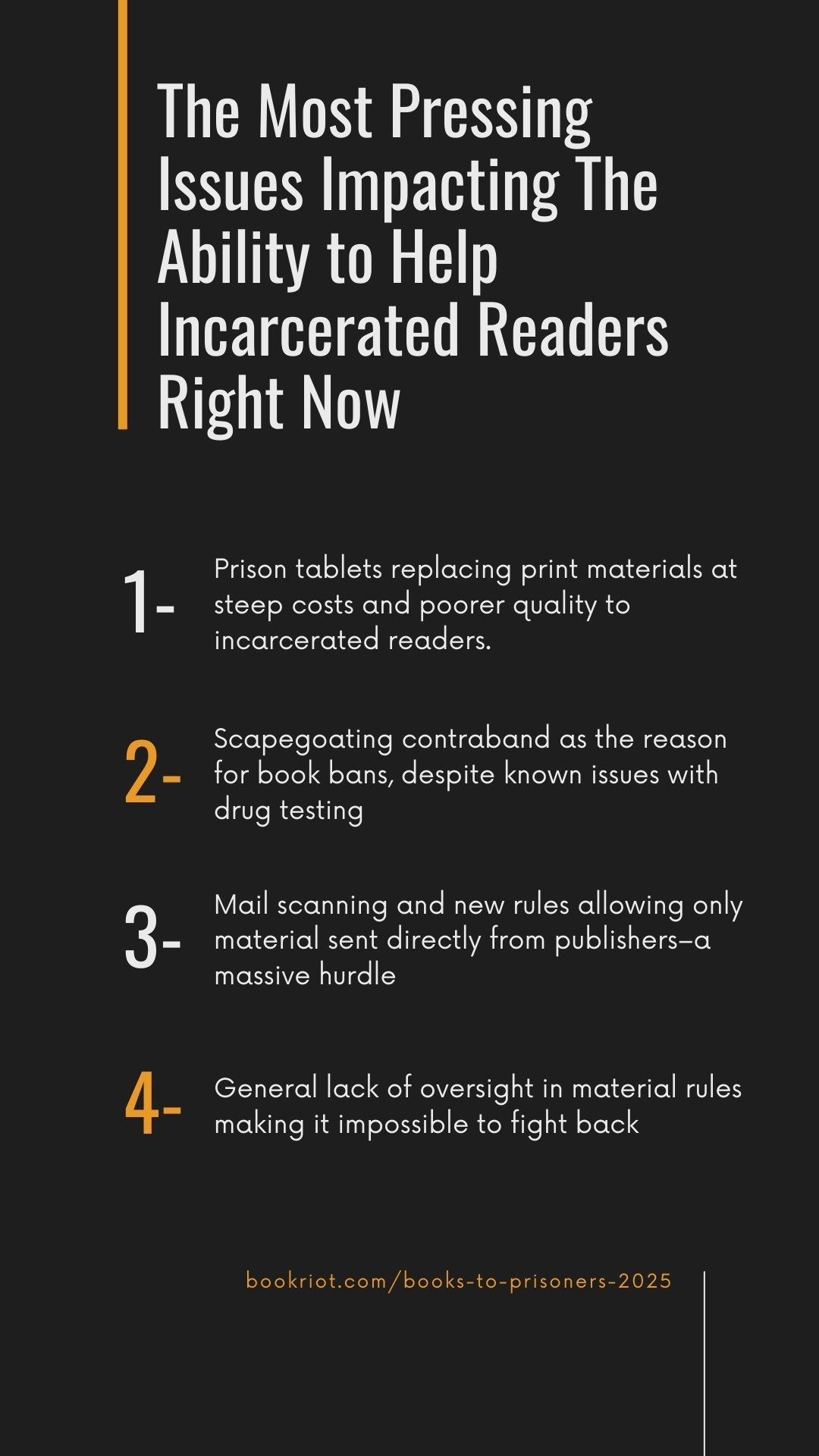

Volunteer groups like BTP have operated since 1972. For fifty years, we’ve assisted tens of thousands of incarcerated readers. However, we face constant battles to maintain our services. Jails and prisons sporadically restrict access from publishers and community groups like ours (what advocates have termed “content-neutral censorship”), and facilities have incredible latitude to censor the contents of books under an all-purpose rationale of “safety and security”. Under such questionable “security concerns”, prisons have banned maps of the moon, encyclopedias of dog breeds, and books about learning to draw birds, among many other plainly overreaching bans. Even more troubling, research shows that jails and prisons routinely target books about Black history and civil rights activism under those same alleged security concerns. The result is that prison book programs spend substantial time trying to stay ahead of new restrictions and carefully stocking their libraries with books most likely to make it past censors—all of which takes away from the core mission of providing free books upon request to incarcerated readers.

Restrictions on physical books have escalated in recent years, as jails and prisons search for ways to curb drug contraband inside facilities. This search has led some facilities to completely ban books from being mailed to people. One of the most drastic recent cases, Bernalillo County Metropolitan Detention Center in New Mexico, not only completely banned physical books from being mailed in July 2025, it confiscated personal property, including books, that people had been keeping in their cells. The alternative offered in such facilities is often a tablet that private companies contract with prison and jail systems to provide. Investigations and lived experiences reveal that books on these tablets amount to outdated public domain books scraped from Project Gutenberg and overpriced ebooks from which companies controlling the tablet profit while they continue to push a narrative that books are major sources of contraband.

In conjunction with prison tablets, many facilities have adopted mail scanning. Under mail scanning, people who are incarcerated no longer directly receive letters from loved ones. Instead, mail is shipped to a second location, where pages are scanned and sent back in a digital format. Advocates decry delays in receiving mail, low quality scans, privacy concerns, limited accessibility (a person must be using a tablet to view their mail), and, ultimately, the dehumanizing effect of preventing a person from holding a letter from their spouse or child. Compounding these grievances, an investigation from the New York City Department of Investigation in 2023 demonstrated that field tests for drug contraband on mail items produced a rate of false positives of 85%. In other words, the majority of the time that a scanner claims that a letter contains drugs, the test is wrong. Yet these baseless tests are used to deploy damaging policies, such as an emergency rule that went into effect at the Illinois Department of Corrections on August 14, 2025. This emergency rule implements mail scanning at all Illinois prisons and prohibits all books from being mailed to Illinois prisons, except if purchased from publishers. Prison book programs have, overnight, been banned in Illinois prisons, and unless a person has the money to purchase a book from a publisher, they will lose access to books by mail.

This is part of a larger issue: a general lack of oversight in prisons and jails and lack of capacity for advocates to fight back against unjust rules. For example, Wisconsin Books to Prisoners has been working tirelessly since 2024 to reinstate prison book programs in Wisconsin after the state’s Department of Corrections abruptly banned used books, claiming increased drug contraband. Books to Prisoners Seattle fought back after the Washington Department of Corrections attempted a similar sudden policy in 2019—and won. A public records request at the time showed the alleged drug contraband was actually based on a poorly constructed database search that returned incidents unconnected with books, much less books mailed by prison book programs. . However, victories are reliant on efforts from volunteers, journalists, and, often, legal intervention. Without concerted campaigns to establish basic oversight to prevent prison and jail censorship and to prevent bad policy decisions based on faulty data, jails and prisons will continue to exert unchecked power to the detriment of incarcerated readers.

This is part of a larger issue: a general lack of oversight in prisons and jails and lack of capacity for advocates to fight back against unjust rules. For example, Wisconsin Books to Prisoners has been working tirelessly since 2024 to reinstate prison book programs in Wisconsin after the state’s Department of Corrections abruptly banned used books, claiming increased drug contraband. Books to Prisoners Seattle fought back after the Washington Department of Corrections attempted a similar sudden policy in 2019—and won. A public records request at the time showed the alleged drug contraband was actually based on a poorly constructed database search that returned incidents unconnected with books, much less books mailed by prison book programs. However, victories are reliant on efforts from volunteers, journalists, and, often, legal intervention. Without concerted campaigns to establish basic oversight to prevent prison and jail censorship and to prevent bad policy decisions based on faulty data, jails and prisons will continue to exert unchecked power to the detriment of incarcerated readers.

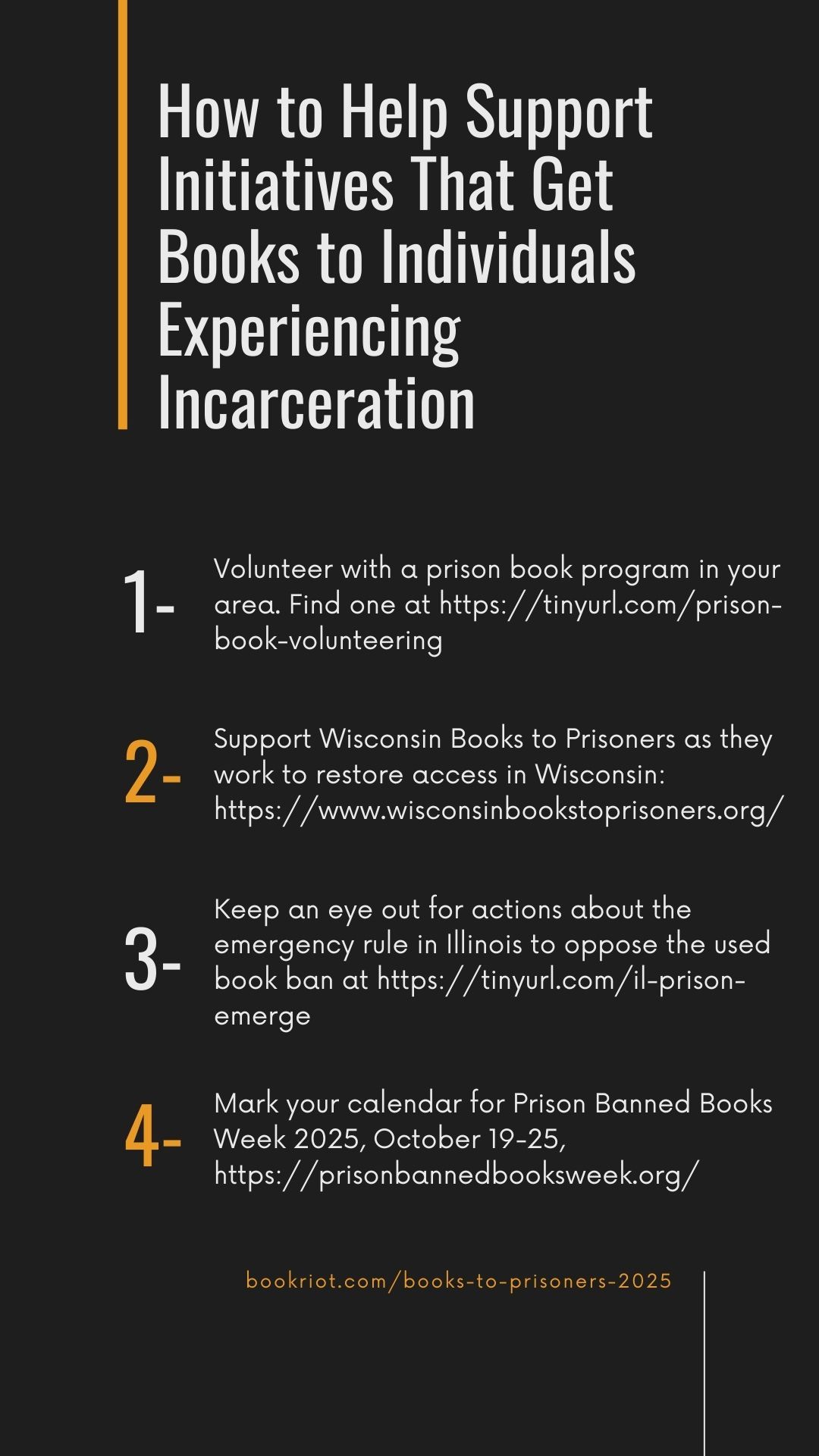

If you’re interested in helping to grow the base of support needed now:

Volunteer with a prison book program in your area As part of its Expanding Information Access for Incarcerated People Initiative, the San Francisco Public Library maintains a map of prison book programs and other interesting initiatives to support information access for incarcerated people. This page also contains many other fantastic resources about this area, including training videos! Support Wisconsin Books to Prisoners as they work to restore access in Wisconsin Under a pilot program newly allowed by the Wisconsin DOC, Wisconsin Books to Prisoners can send new books only. Consider making a purchase from their wishlist or supporting their ongoing need for rent and postage. Keep an eye out for actions about the emergency rule in Illinois to oppose the used book ban This is still a developing story, but Illinois groups are working to coordinate a response, including an open letter submitted by legal entities. Public engagement consistently has been the most effective tool to overturn book bans. Mark your calendar for Prison Banned Books Week 2025 (October 19-25, 2025) Prison book programs will be partnering with local bookstores for matching grants to help buy new books Share posts and other special content about prison censorship that week! |

Michelle began volunteering with Books to Prisoners Seattle in 2012 while completing a Master of Library and Information Science. From 2014 to 2017, she served as the nonprofit’s inaugural Program Coordinator and continues to serve on its board. Through research, writings, interviews, and the coordination of public campaigns, she has contributed to nationwide efforts to increase access to information inside carceral facilities.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·