From a new law review article with that name, by Andy Smarick (Manhattan Institute):

During congressional testimony in 1999, the late Justice David Souter explained that only those who graduated from one of the nation's most elite law schools would be qualified for a precious Supreme Court clerkship. He considered it risky to hire from "outside the well-trodden paths." Earlier in the same hearing, he referred to Chief Justice Rehnquist's well-known and different view: that the top performers at a wide array of law schools are "fungible." That is, the most elite schools might have more of the highest-ability students, but extraordinary talent can be found far and wide.

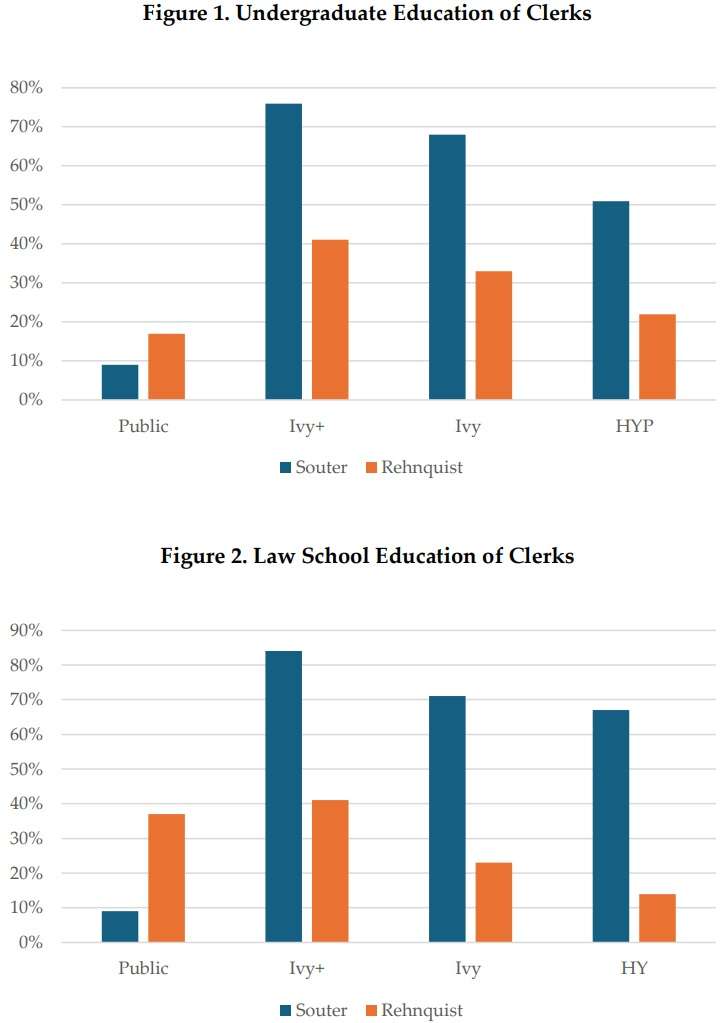

These competing visions of legal potential are reified by Justice Souter's and Chief Justice Rehnquist's actual histories of clerk hiring. Since 1980, no justice pulled from a narrower sliver of schools than Justice Souter; Chief Justice Rehnquist hired from one of the largest pools. This finding, however, is not limited to these two justices or even to justices on the United States Supreme Court. On the contrary, the legal profession appears split between the elitist Souterian vision and the egalitarian Rehnquistian vision.

The consequence is two distinct prestigious legal circles. One has graduates of a vast array of undergraduate and law schools, including flagship public schools, regional public schools, small liberal arts schools, larger selective private schools, and more. The other is dominated by graduates of a strikingly slender set of private institutions, namely Ivy and "Ivy+" schools. {My studies follow the recent convention of adding four highly selective private schools (Chicago, Duke, MIT, and Stanford) to the eight Ivies to form an "Ivy+" category.}

At least two factors seem to have created and maintained these separate circles. The first is the education of "choosers," the gatekeepers for elite professional roles. When Ivy+ graduates are in charge, they overwhelmingly hire Ivy+ graduates. They seem to hold the Souterian view that talent is concentrated in the types of schools they attended (Justice Souter graduated from Harvard College and Harvard Law School). When choosers are educated at a broader array of schools, the Rehnquistian vision predominates: individuals are hired from a broader array of schools.

The second factor is geography. In most of the nation, the top ranks of the legal profession are mostly filled by individuals from nearby public and private universities. Ivy+ graduates are few and far between. In only a few states, such as California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York, are Ivy+ degrees prevalent.

The existence of two elite legal circles—and the reasons why they both exist—matters. First, as a practical matter, it affects the opportunities (or lack thereof) available to law students and early-career lawyers. Although the top graduates of non-Ivy+ schools can rise to professional prominence in the legal community across most of America, they are at a severe disadvantage in a few locations and when Ivy+ graduates are in charge of hiring decisions. For instance, Ivy+ justices are significantly less willing to hire clerks from non-Ivy+ schools. As such, talented graduates of most of America's colleges and law schools appear to be systemically denied a fair shot. This also means that some of our legal institutions have a paucity of talented individuals from such schools.

Second, these two elite legal circles, because they have different educational profiles, may well differ in other meaningful, predictable ways. For instance, affluent, connected students have an advantage in the Ivy+ application-and-acceptance process. Those students then spend years on campuses located in a sliver of America and with cultural sensibilities different than much of America. They then disproportionately build careers in a handful of East Coast, urban settings (e.g., Boston, New York, Washington, D.C.). This is not the experience of most legal leaders.

America could, as a result, have two elite legal circles with significantly different instincts about religion and technocracy, knowledge of rural America and regional traditions, and views on politics, federalism, localism, civil society, and so on. At minimum, we should recognize the possibility, perhaps the likelihood, that these different legal circles think differently about law and policy. In what follows, I describe the differences between the "Souterian" and "Rehnquistian" views of talent, show how these differences manifest in a variety of important legal roles at the federal and state level, and describe the influence of several notable factors, including geography, ideology, and "feeder judges." …

I will close with one question and two observations. The question relates to whether and how this difference in educational profiles manifests in different professional decisions and behavior. Future research should study the extent to which these different circles reflect different politics, cultural sensibilities, and more due to their members' different academic backgrounds. It is hard to justify different segments of the legal community's top ranks having dramatically different backgrounds. But if that is the case, we should be aware of it and understand the consequences.

The first observation is that many public and non-Ivy+ private schools are producing outstanding future leaders even though those schools' graduates are all but ignored by Souterian selectors. That is, non-Ivy+ justices and selection systems in most states find talented individuals in non-Ivy+ schools to serve in important posts. The most prominent of those schools are flagship public universities. For instance, University of Mississippi School of Law currently has nine graduates on state supreme courts. Only Harvard Law and Yale Law have more graduates as state justices. But only one Mississippi Law graduate has been a Supreme Court clerk since 1980. In that same time, Harvard Law and Yale Law have had 748 clerks combined.

The law schools of Montana, Nebraska, South Carolina, West Virginia, Wyoming, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Arkansas educated thirty-six current state supreme court justices. But not a single Supreme Court clerk in the last forty-five years came from any of those schools. The list of undercapitalized non-flagship publics includes Arizona State, Purdue, Michigan State, Miami (Ohio), and UCLA. The list of undercapitalized private universities includes Boston College, BYU, Creighton, Denver, Drake, Marquette, Seton Hall, St. Olaf, and Willamette University.

The other observation is that the Souterian approach to talent shortchanges countless individuals. Extraordinarily able seventeen-year-olds choose to go to non-Ivy+ colleges for many reasons. Many excel at those schools as undergraduates. Many top graduates of non-Ivy+ colleges choose to go to non-Ivy+ law schools for many reasons. Many excel at those law schools. These individuals will find leadership opportunities in some places, but they will be at a severe disadvantage when Souterians are in charge. Of Justice Souter's ninety clerks only three were double-public graduates. Of Justice Kagan's sixty-one clerks, only one was a double-public school graduate.

To be a Rehnquistian does not mean discriminating against the graduates of elite private schools. Indeed, in most Rehnquistian states, Ivy+ graduates are still overrepresented in legal leadership roles. The most Rehnquistian justices—Rehnquist included—hire a significantly higher percentage of Ivy+ college and law school grads than the Ivy+ percentage of the college- and law-school-graduate population. But being a Rehnquistian does mean looking for and hiring talented individuals from a wide array of schools. It is not clear whether Souterians doubt the existence of such individuals or whether they are not interested in looking for or hiring them. Whatever the reason, it can, and should, change.

The post "The Souterian and Rehnquistian Views of Legal Talent" appeared first on Reason.com.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·