If you were to walk down Lackrow Boulevard in Dunwall—taking care not to linger outside The Black Friar, the dilapidated hotel where the Hatters Gang conduct their business in the legal district—you might stop at number 131. These are the premises of the company who build audiograph players: the rudimentary recording devices which capture the voices spoken into them, and offer scratchy, echoey playback via punchcards. All over the city, audiographs hold the private thoughts of lords and admirals, the final words of gangsters and royal caretakers. The inner life that elevates NPCs to characters who haunt their levels long after they're ragdolled.

The name above the door of that business? AudioLog.

It's only fitting, since the inventor of the audiolog was a writer on both Dishonored and its 2016 sequel. During the development of System Shock, Austin Grossman had helped figure out the fundamentals of the genre we now call the immersive sim. As a writer on Deus Ex, he'd contributed to its indelible influence as a smart, funny, and above all malleable story game. And later, he wrote You—one of the definitive videogame novels, and in many ways a fictionalised account of what it was like to work at Looking Glass Studios in the '90s.

It's hard to imagine anyone more qualified to join the Dishonored writing team. Yet when he did, Grossman didn't quite get it. "When I came in, it sounded a little bit ridiculous," he says. "They were still hammering out some of the details of the world. There were the whales, there was the Outsider, there was magic. Everything was super dark. It sounded kind of like a mess. I was like, 'How is any of this gonna cohere into a world that anybody believes in?'"

When I came in, it sounded a little bit ridiculous.

Austin Grossman

Much of Dishonored's writing and world-building originated with Harvey Smith, the game's co-creative director, who had a "really, really strong idea creatively of what he wanted to do".

"My job was just to channel that," Grossman says. "Nothing I wrote in Dishonored remotely resembles anything I write in my own creative work. But that was the fun of it. It was like, 'What if I were Cormac McCarthy? What if I just wanted to write everything as dark as possible?'"

Alongside Smith and Grossman, the team brought in Terri Brosius. Most famous for her chilling voice role as SHODAN in System Shock, Brosius was also a seasoned writer who had shaped the Lynchian tone of the Thief games. She's still working with Grossman today, on the multiplayer imsim Thick as Thieves. "She's immensely fun," Grossman says. "Immensely talented."

There was some resistance on the Arkane team to the idea that Dishonored's setting could be categorised alongside existing genre fiction. "There was this whole funny business where they were like, 'It's not steampunk. Shut up, don't say steampunk. We're not doing steampunk,'" Grossman says. "And it's like, 'OK, but look at your world. It kind of is steampunk.' Sometimes in game development, you just get hung up on a matter of principle. And then a year later, you realise, 'Why am I drawing that line when it's obvious?'"

Grossman found his own tonal lodestar in an unlikely spot. "I'll tell you the truth, which I don't think I ever told Harvey," he says. "My personal style guide was Sweeney Todd, the Stephen Sondheim musical. I ripped off a couple phrases from it that any Sweeney Todd fan will have recognised. It was super dark, Victorian, with this black humour to it. It just absolutely fit right in. It's perfect."

So much of Dishonored seemed to match the model established by Sondheim. Take the wicked vices of its villains, who Corvo tore down in a mission of revenge. "Then he finds out at the end that the world is different than he thought it was," Grossman says. "It all works. But I felt like discussing that in public might disrupt the perception of Dishonored."

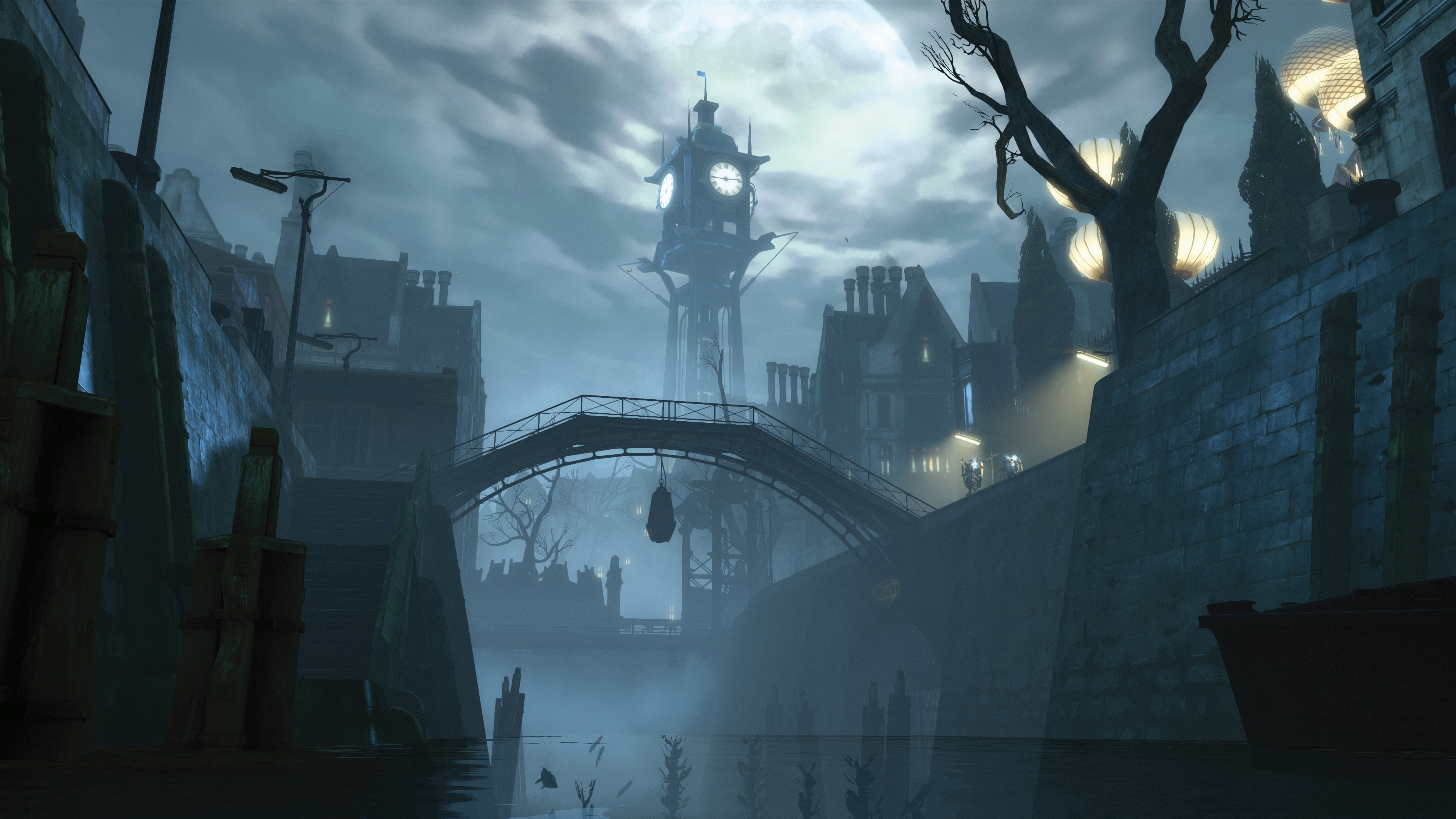

Little by little, by means secret and out in the open, the world of Dunwall began to not only cohere but become one of gaming's great settings—a densely atmospheric place that would live on in players' minds long after the credits rolled. Grossman had a great experience, and enjoyed writing for the Outsider, the figure from the Void who grants Corvo his reality-bending abilities.

"Although it was maddening how slowly the actor reads those speeches," Grossman says. "I wish we could just crank it to 1.5 speed, because I can't sit through them, even though I like a bunch of the stuff I wrote really a lot."

Even a switch in the Outsider's actor for the sequel didn't end Grossman's dissatisfaction. "I was never a fan of how those were delivered and staged," he says. "But they were certainly cool to write."

Brosius and Grossman came up with the Heart. A strange and supernatural totem, this human organ was carried around by protagonist Corvo throughout the game. "It was so fun to write for that thing," Grossman says. "And that's why we had it." When squeezed, the Heart offered up mournful reflections on the state of Dunwall—and when pointed at a person, revealed sometimes terrible secrets. "Unless he dies tonight," the Heart might say of a city guard, "he will kill twice more before ending his own life."

Since Dishonored offered both lethal and avoidant means of handling threats, many players consulted the Heart to decide how to deal with the NPCs in front of them. Those decisions fed into a larger, unseen calculation that determined whether the plague-and-tyranny-ridden city would ultimately claw back toward the light or slide sideways into anarchy.

"The whole high chaos, low chaos thing," Grossman says. "I think everybody liked that and was never fully satisfied. Because obviously, you don't get enough feedback as you're going through, as to where you are on that scale, right? You crossed a chaos line, but you don't really get told."

Of course, if Dishonored had let players see that scale as they navigated Dunwall, they were much more likely to try and optimise it—engaging in a metagame rather than embracing the story.

If you work in narrative design, it is one of the unanswerables.

Austin Grossman

"If you work in narrative design, it is one of the unanswerables," Grossman says. "Whether you expose the numbers for that kind of thing, and then it's a game, or you don't expose the numbers, and players feel like they don't understand the consequences of their actions until too late. There's two ways of doing that, neither of which really works. It's interesting about narrative design, it's still an immature field."

Nevertheless, Dishonored struck a chord with millions, and Grossman got to work on both a brilliant DLC campaign—which starred Corvo's onetime enemy, the assassin Daud—and Dishonored 2, which PC Gamer gave a coveted 93%.

"I think it was really smart," he says of the sequel, which gave players the choice of starring as Corvo or Dunwall's empress, Emily Kaldwin. "Letting you play as either person really worked." The decision to decamp from Dunwall to another island in the empire, the sunbaked Serkonos, was another change Grossman was happy about. "The fact that we went to Karnaca is really cool," he says. "Dunwall is great, but it's super claustrophobic. Getting out of there was great."

Grossman wanted to visit every island in Arkane's universe—which canonically includes snowy, glacial Tyvia in the north, and the jungly Pandyssian Continent, which defies colonisation. "I really wanted Dishonored 3 to happen. I wonder if someday it will. Because the whole world that they built is fascinating," Grossman says. "I did want to experiment with a Dishonored game that had a slightly different tone."

If there's a weakness to the Dishonored games, in Grossman's opinion, it's that they're always steering toward an ultra-dark mood. "And I thought, someone somewhere in the Dishonored world must have had a good day at some point in their lives," he says. "I wanted to see a little of that. Because it was always trying to top itself and say, 'OK, what's even darker.' At some point you run out of that. And I think a varied tone in a Dishonored game would have been really fun to do."

There's got to be a climate somewhere in the Isles that hosts neither rats nor bloodflies, surely? "You know, let's not go crazy," Grossman deadpans. "There's always going to be some vicious, murderous pest in any city, because otherwise, how would you even know you're in a Dishonored game?"

Since Grossman worked on the series, Arkane has confirmed that the time-warped island where Deathloop takes place belongs to the Dishonored universe—only, in its far-future. "So I guess that's Dishonored 3," Grossman says. "The fact that Dishonored and Deathloop are a shared world, that is so freaking awesome. I'm combing through that game to find any kind of clear reference on that, but they've said that it's true."

In some senses, Deathloop feels like an answer to the narrative design problem Grossman identifies in Dishonored. By trapping players in a resetting timeloop, Arkane frees us from the responsibility of deciding who ultimately lives or dies.

"But it also borrows the idea that there's this pantheon of personalities, right, that are each screwed up in their own way, that you have to murder," Grossman says. "Those characters are a little more rounded, a little more deeply drawn, I think, than the Dishonored villains."

The revenge and murder motif that Dishonored and Deathloop share is a powerful motivator—one that Grossman considers lacking in Arkane Austin's space station adventure, Prey. "I think the reason you never hear about Prey is that the story doesn't have the same emotional weight," he says. "It's just not driven the same way. Because it's a great immersive open world. It's one of those games where story is the missing piece, I think."

Today, Grossman says that writing for the Dishonored games was a privilege. "But like I said, I would never have made the call that it was the most successful game I ever worked on," he says. "There was no indication of that, so there's a good lesson there somewhere."

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·