Patricio Ferrari and Nikola Madžirov

Patricio Ferrari and Nikola Madžirov

On April 17, 2025, I spoke with poet Nikola Madžirov at the New York Public Library’s Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library, following a moving performance by Madžirov and Grammy-nominated singer, songwriter, and composer Becca Stevens. The conversation and performance marked the launch of Limelight Poetry’s World Poetry Salon—a new series founded by poet Wang Yin that invites outstanding poets and artists from around the world to share their work across languages and artistic disciplines.

Limelight Poetry is dedicated to showcasing poetry in underrepresented languages and creating opportunities for dialogue between poetry, music, and translation. Drawing on the city’s rich cultural life, the series fosters global exchange while welcoming audiences into a vibrant and intimate space of poetic encounter.

In this inaugural event, we discussed language, migration, memory, and return—as themes threaded through Madžirov’s life and poetry—and the collaborative possibilities that emerge when poems are reimagined through sound. [Editorial note: You can watch archived video of the event on YouTube here.]

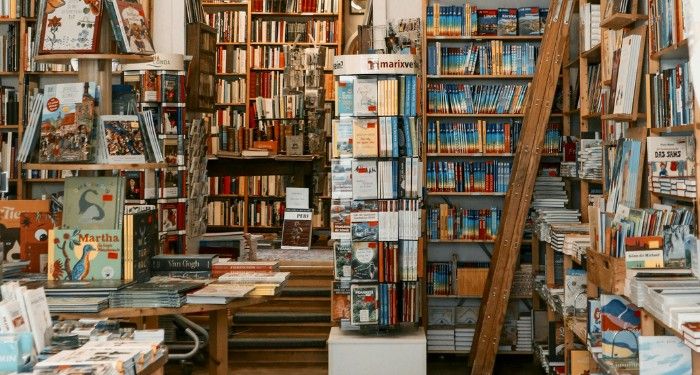

Patricio Ferrari: Good evening, everyone. It is a pleasure to be here in this—and I’m going to borrow a word you heard tonight from the Slavic—dom of words. A house of language. A house of millions of objects—fifty-five million, in fact—including volumes of books, autographs, and photographs—all housed here at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library.

In a city like New York, where diversity is celebrated across so many institutions, it feels especially meaningful to gather for this occasion. I’m delighted to open this inaugural event with Nikola Madžirov, with Becca Stevens and Wang Yin, and with friends and students—both here in person and across borders, livestreaming from around the world: not only the US but also Africa, Europe, and Asia.

Thank you for your support—and for your presence today—because here, we are bringing poetry back to its roots.

If you’re wondering what lyric poetry is, this is it: song, sound, the voice shared and heard live. In a language that is also ours. A remnant of another age, as Nikola writes in his work.

We’re here because collaboration matters. We’re here because translation matters. And we’re here because generosity matters—and because listening to one another across borders, across flags, from all walks and accents of life, matters now more than ever.

I’d like to begin this conversation with Nikola’s surname. Some poets, you know, carry in their last names—and we’ll get to that in a moment—a kind of prefigured, even predestined poetics. I’d love Nikola to tell us a little bit about his last name and how, in a way, it embodies so much of what he is—not only as a poet, but as a human being.

Madžirov: Thank you, Patricio. First, thank you all for being here. It’s such a pleasure. Thank you for your silence. It gave me resounding support, especially being onstage for the first time with Becca Stevens. Luckily, I am still jet-lagged—it’s much easier to talk when you’re still in the air, and we’re seven floors up.

When you say “last name,” it sounds apocalyptic—people talk more often about last days or last words. Maybe that’s why I write poetry. I think with each new poem, we’re reborn. It goes against the idea that writing is only about longing for eternity . . . Eternity has nothing to do with being reborn.

My last name is Madžirov. It comes from Arabic—muhājir—“madžir” being the shortened form, meaning “migrant” or “a person without a home.” And yet, the first poem I read this evening is titled “Home.” Nomen est omen. I didn’t know about the meaning of “madžir” when I first started running away from home, in pajamas and in my father’s oversized shoes, trying to disappear into the womb of the city. And yet, if someone tried to take me back home, I would try to forget even the name of my street.

I inherited my last name from ancestors who were refugees of the Balkan wars about a hundred years ago. Behind each new map of the Balkans, there is always a war—each becomes a new layer of lived existence. I realized that my first trip wasn’t a journey—it was an escape. Like my writing, it wasn’t a journey for discovering “eternity.” It was simply an attempt not to forget.

Before becoming Madžirov, my family name was Stamenov—meaning “very stable” or “resistant.” After the Balkan Wars [of the 1990s], to avoid the slaughter, they had to flee. Because after every official war, there are many unofficial ones that go unrecorded. Languages and cultures are erased, and the only memory that stays alive is the personal story.

That’s why I trust personal stories more than official histories. That’s why I write poetry and I don’t trust statistics.

There are many people without a home, whose memory becomes a kind of heritage. My ancestors kept their house key in the same jar where they kept their medicine. They truly believed this could heal their pain and nostalgia—the key to a door that no longer existed. I inherited not just that ruined door but many other nonexistent doors. That’s why I’m here.

My ancestors kept their house key in the same jar where they kept their medicine. They truly believed this could heal their pain and nostalgia.

Ferrari: And Nikola, speaking of roots—both personal and linguistic—let’s return to your hometown. Strumica: a place you returned to after many years, located south of Skopje, in the Republic of North Macedonia—a place with over six thousand years of human presence, of remnants, of traces.

What I find fascinating—before we enter your work more fully—is how much of it circles around dom, or home. But never descriptively. You’re never merely depicting. When it does appear, it arrives in the form of metaphors.

What’s even more striking is how the places you evoke resist direct representation. They vanish, flicker, hover—spectral, yes, but never hollow.

And this—something we’ll return to when we touch on German expressionism—I found especially moving: your writing clings to and resists the present and the past at once. Memory runs through all of it.

So—Strumica.

Madžirov: Patricio pronounced the name of the city correctly—many people say “Strumika” or “Strumicha.” I remember when I met Adam Zagajewski in Berlin, I pronounced his city of birth as “Lavov.” After a long pause, he said he was now richer for having a new birthplace.

I feel when we pronounce a city differently, we gain another place of existence. Maybe that’s why invaders start by changing the names of rivers, cities, people—only afterward do they speak of love and understanding.

Wenders said that places are crucial to his films—he searches for a place first, then the story comes. Place holds the memory.

Wenders said that places are crucial to his films—he searches for a place first, then the story comes. Place holds the memory.

The best psychiatrist might tell you to change your place first, and then talk about inner change. My grandmother, who worked as a hospital cleaner and was therefore not afraid of death, once said to me: “Home is where there is smoke from the chimney.” As a child, that made no sense—because to see the smoke, you had to step outside. So, leaving became the poetics of my breath. Sometimes, leaving is a stronger sign of life than staying.

Leaving became the poetics of my breath. Sometimes, leaving is a stronger sign of life than staying.

The phenomenon of return gives us the ability to name a place “home”—a place to which we belong. When you’re a tourist, you mark on the map every place you've visited, but you rarely return. When you do return or—most importantly, perhaps—when you return to your birthplace or your home, it becomes a map of an undiscovered world.

Ferrari: And the voice—at least the inner dialogue—changes when we do return.

Madžirov: It turns into silence that cannot be inherited . . .

Ferrari: You want to expand on that?

Madžirov: When Cavafy returned to Alexandria, he may have thought that the city had changed—but in fact, he had changed. Absence is essential to understanding not only what’s missing, but the significance of your own presence.

When we enter a library like the New York Public Library, the first feeling that fills your blood is the disappointment—that you haven’t read all these books. Then comes the fear: that you won’t continue writing, because everything has already been written. And then, in the midst of that mental paralysis, you notice that one book is missing from the shelf. You start imagining its title, the life of the person reading it. And then you wish that the missing book were your own. That absence gives birth to the desire to leave a trace—to write over the already-written.

Ferrari: Indeed. And when we speak of fading—or of returning to a place to find that what once was is no longer—it’s hard not to think of memory.

Reading your work, an image came to mind: the ellipsis—as a poetics of return, of memory reentering. But not as a time loop, not linear. A memory that resists chronology.

Of course, many of us are familiar with Cien años de soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude). García Márquez does it masterfully. But reading your work, I was reminded of a lesser-known novel: La lluvia amarilla, by Julio Llamazares, the Spanish writer born in rural León. The book unfolds as a monologue by the last inhabitant of a village in northern Spain—everything is fading, including himself. And yet, that very moment of fading brushes up against the present.

So this idea of memory resisting linearity—existing in both past and present—is something like a time-outside-of-time, a place-outside-of-place.

And finally, your work also brought to mind Maria Stepanova’s In Memory of Memory. Through her aunt—and other interlocutors from the past—she explores diaries, photos, archives, and finds herself in the present, rubbing up against a past that isn’t strictly chronological.

So, “remnants of another age,” to borrow the title from the English translation of your collection, carry us into something larger than history—yet always anchored in a particular place. That might sound contradictory, but I hope it makes sense.

Madžirov: Yes. That brings us to Borges and his Aleph—a point in space that contains all other spaces at once.

Maria Stepanova’s remarkable book reveals the fleeting nature of memory. We reconstruct memory depending on place, mood, and to whom we’re speaking. We want to believe in the imperfection of memory, because it gives us hope as writers.

Linear time has never been a concern for me. They say, “Nothing is older than yesterday’s newspaper.” My friend’s grandfather used to say, “What you can do tomorrow, it’s better not to do at all.” Yesterday and tomorrow are too close for my writing—I long for distance, because distance makes room for memory.

Yesterday and tomorrow are too close for my writing—I long for distance, because distance makes room for memory.

Time is like a circle with an open door. Memories exist so that we reconstruct them—often just to feel safe.

When we try to repeat something in order to remember it, we enter the realm of ritual. Mircea Eliade calls this the “eternal return.”

We remember what becomes ritual, but we forget what becomes routine. We go back to check if we locked the door, turned off the light, or put on the right facial expression before an important meeting. That’s a different kind of body memory.

This can’t be explained in poetry. That’s why poetry lives more within the realm of ritual.

Ferrari: And speaking of ritual—as both act and metaphor—it connects us to rhythm; it instantiates rhythm, doesn’t it?

Rhythm is repetition in time. We break from it—and then we return. Your work—like any enduring poetry—is full of rhythm. And you achieve it in many ways.

There’s sonic repetition—we hear that clearly in your poems. Some lines repeat. Sometimes even half-lines recur across the work. But there’s also repetition through imagery, through figures of speech.

You often employ similes—which, though sometimes overlooked, are themselves a form of nonphonic rhythm: a pattern of likeness.

And this brings me to something essential in your work: your poems don’t rely on narrative—not in the traditional sense. There are no extended narrative arcs. Time and memory in your poetry emerge, not through story, but through image—through metaphor.

When you take us back to Strumica, you do so through images: the wandering child with the moon at a distance, the graves, the boy who is not recognized. It’s a place and not a place. It’s spectral. A return—but one that’s veiled.

And this rhythm—this returning and breaking—reminded me of Georg Trakl and German expressionism, especially his “Song of the Departed,” with the line: “The patient one wakes on the petrified threshold.”

You’ve returned, in different poems, to a handful of talismanic images: the home, the hand . . . but especially the threshold.

If you’d like to speak to that—and perhaps share the story you once told Ilya Kaminsky—I trust the audience would love to hear it.

Madžirov: Тhank you, Patricio. I’m sorry I’ll have to be personal because Patricio’s questions are profound.

There was one image that I remember when I was a child: I once saw an old lady standing on the threshold of a church. She was crossing, but I couldn’t tell if she was going in or coming out. Maybe she wanted to light a candle for someone who wasn’t there. Or she didn’t want to enter because she was afraid of eternity.

I remember another threshold story. I come from a region prone to earthquakes. Some of you may remember the strong 1963 earthquake in Skopje—over a thousand people died. My grandmother always told me: as soon as the ground starts shaking, don’t run outside, and don’t lie on the floor. Stand in the doorway—the threshold. It’s the safest place.

My hometown, Strumica, is near the borders of Bulgaria and Greece. I grew up with borders and mountains, always questioning the limits of thoughts and what lies behind the visible. Those in-between zones became my safest home—the threshold of my existence.

Ferrari: And this brave man, now telling us about his grandmother and the threshold . . .

Nikola, I’d like to invite you—if you’re willing—to close with one more threshold story: the one before the hospital. When that line came to you for tonight’s final poem, “The Eye”—and how, in that moment, the threshold became the hospital room itself.

Nikola was the only survivor in that room. He contracted Covid during the first year of the pandemic—and we are incredibly lucky to have him with us here today.

Would you share how that moment shaped your work? First, because—almost intuitively—you had already written “The Eye.” And then later, how your collaboration with Becca unfolded while you were still in the hospital.

Madžirov: I spent several months in the hospital, struggling for every breath. Since then, I’ve come to believe that in the beginning, it wasn’t the Word—it was the Breath.

I was the only survivor in my room. The doctors would bring in a movable white wooden screen between the beds before someone died, so I wouldn’t see the face of death waiting for me around the corner. The white wall stood like a sheet of white paper—between the breath and the silence.

Even now, when doctors look at my CT scans, they see many scars across the lungs and wonder how I can still breathe. But I tell them that those aren’t scars but rather letters from an unknown alphabet, which still look beautiful on the scans.

Ferrari: And during that time—

Madžirov (breaking in): —their time: time also belongs to the dead—

Ferrari (continuing): —when you were there, Becca—

Madžirov (breaking in): —Becca found the poem “The Eye” online while I was in the hospital. The song you heard tonight, “The Eye”—composed by Becca and Michael League from Snarky Puppy—was written while I was trying to breathe with my eyes closed. She brought the words back to their source: to music, to breath.

When I write, I feel like I’m returning the words to their home. And that home can be a sound, an image, or a silence.

When I write, I feel like I’m returning the words to their home.

My grandmother—who was blind in one eye and saw the world more deeply—used to sing the same songs differently each time. Whenever my father tried to write them down, she would stop him and say: “Don’t kill the songs. Just sing them—a new word may emerge, a new memory arise.” Writing was an execution.

I’ve been traveling and searching intensely for more than twenty years. And yet, my grandmother would tell me that she had visited more countries just by sitting on her old bed in the kitchen.

In the Balkans, you can cross empires, ideologies, and new borders simply by sitting on your chair, older than every tree in the yard.

It was the most dynamic way of existence I’ve ever witnessed: to be rooted somewhere, while borders and skies are constantly shifting around you—with more keys in your pocket than homes in your memory.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·