As a lifelong book lover, I always want to know more about the process of actually making a book. From the ins and outs of writing a manuscript to the fascinating process of cover design, I’m always down and eager to learn more about how books are made. To be honest, I thought I had an overall decent understanding of the process, but recently I realized that I had one glaring blind spot: how are books illustrated? I had no idea. None. So, of course, I set out to find out more with the help of several brilliant, talented folks.

Why illustrate a book?

I used to think of illustrations as something exclusive to children’s books and graphic novels, and although I understood how pivotal art is to those genres, I never considered just how much all books can benefit from a lovely, well-placed illustration. My eureka! moment came when I read Emily Carding’s Seeking Faery, beautifully illustrated by Siolo Thompson. Exploring different types of Fae was fun and interesting on its own, but the process was made so much richer by the vivid illustrations of nature and faeries filling the book. I knew then and there that I wanted to know more.

On its website, Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design says that the role of illustration in storytelling is threefold: understanding, engaging, and remembering. The reasons why are fairly intuitive, although RMCAD does go into detail: illustrations help readers, especially young readers, understand context, and they allow for a more immersive reading experience, facilitating reading recollection in the process.

|

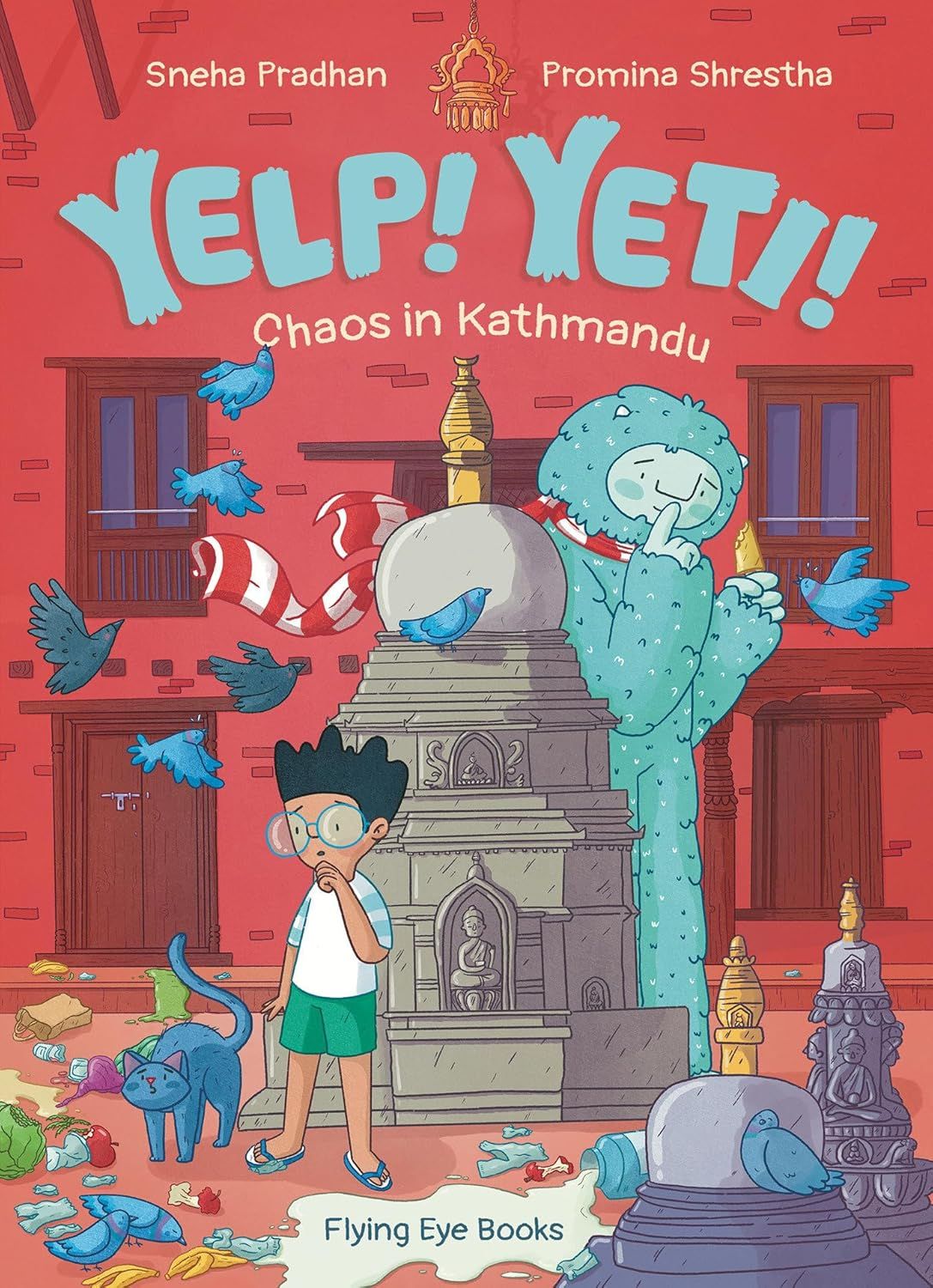

When I mention this to Promina Shresthra, who illustrated the delightful Yelp! Yeti! Chaos in Kathmandu, written by Sneha Pradhan, she explains that for children’s books, “an illustration not only enhances the text, but (…) illustrations actually help you tell the story without using words. (…) We can see the emotions, we can see the background…For example, in the book, we do not need to describe what Kathmandu looks like, and what the architecture looks like, and what the colors of the bricks are, and what’s going on in the streets, because the illustration introduces that whole world, so you can just focus on the story.”

My curiosity was piqued. I knew what illustration does now. But how does it make its way into a book?

First Steps

Well, as it turns out, the process varies, depending on whether it’s run by a publisher or a freelancer. I spoke with the fabulous Monique Sterling, who graciously agreed to lend me her expertise as both a former Senior Designer at Penguin Random House, and a current freelance graphic designer. She pointed out that “in-house book design assignments usually start differently than those contracted as a freelancer.”

This is because, in-house, the art director is usually the one to assign the book to a designer. Said designer, along with a team spearheaded by the editor, sets out to find an illustrator who fits the “tone and feel” of the manuscript. When everyone is satisfied, they reach out to the artist’s agent and inquire about their availability and interest.

Now, as a freelancer, Monique enters a project differently. The artist is typically already chosen and signed by the time she is brought aboard to design the book as a whole.

The Actual Process

Once the artist is already part of the process, they get to work.

But what does this work look like?

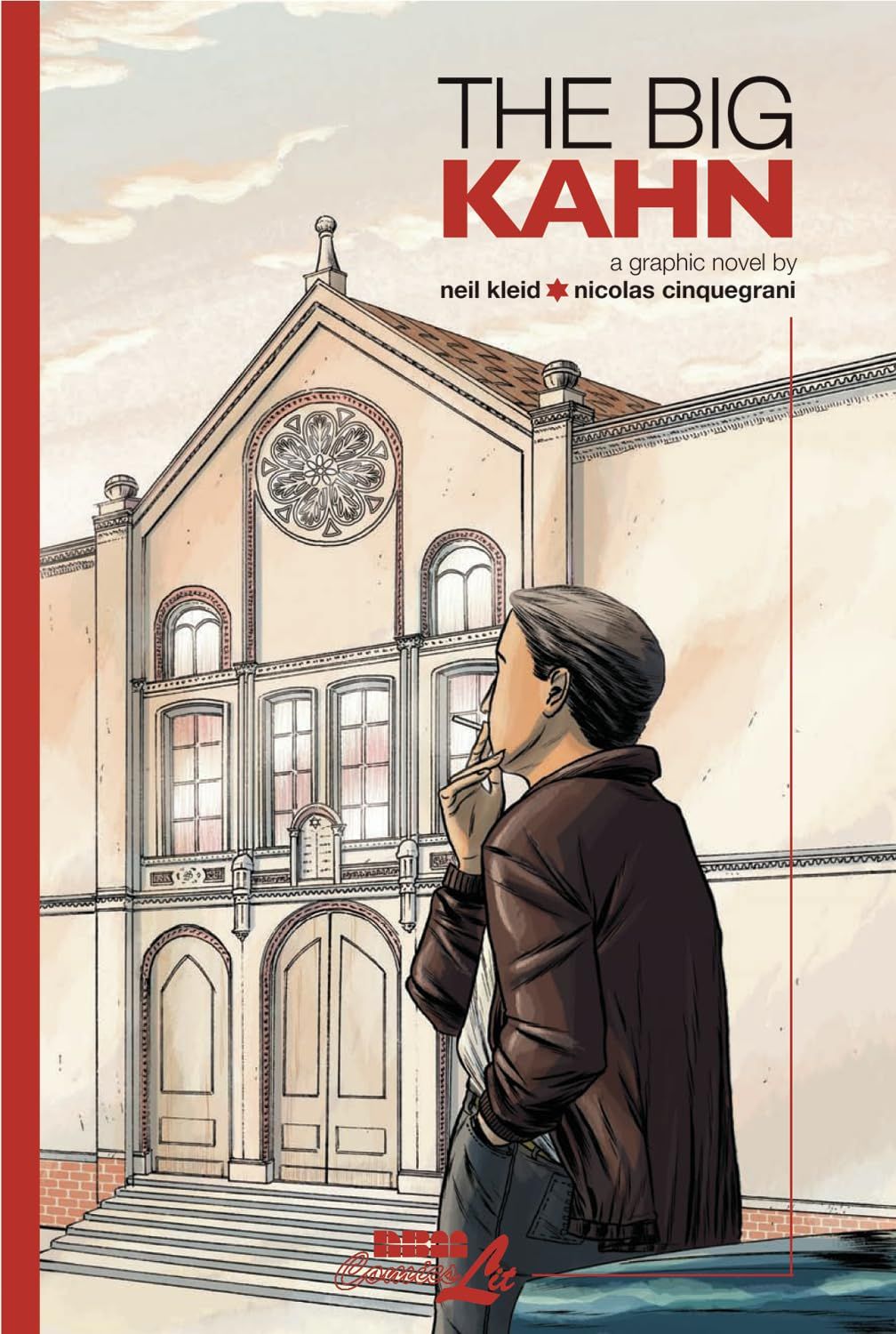

I spoke with artist Nicolas Cinquegrani about his experience illustrating Neil Kleid’s The Big Kahn. He says he “started with rough thumbnail sketches to plan panel layouts, transitions, and text placement. Next, I created full pencil drawings on 11×17 Bristol paper and sent them to the writer and editor for feedback.”

|

Promina adds: “People imagine that when somebody says storyboarding or thumbnails, that they’re fine pieces of work, like they’re fine art, but they’re actually not. They’re very rough sketches. This is the idea you have; you read the text and then you doodle it out. Then you discuss it. For example, I worked with a visual editor, or I discussed it with Sneha at first.”

Promina’s thumbnails were then reviewed by the design team at Flying Kites Book, the book’s publisher, before they moved on to storyboarding. But “even that is roughly drawn in”, she explains.

Do you happen to wonder how artists choose which scenes to illustrate? I did, too. According to Monique, “some authors will submit their manuscripts with art notes, which tend to be short descriptions of what they envision each page or spread to look like.” Even though these are only suggestions that can be downvoted by the publishing team, they “are a great starting point for illustrators!”

In cases where the author didn’t leave any notes, though, “normally it’s up to the illustrator’s vision and expertise to interpret the text. Some artists prefer to start with thumbnails to get a read on if their ideas are working in various areas, like the pacing, variety in perspectives, and rhythm of the story. This is also a good time to gauge whether a scene should be changed altogether before moving on to sketches.”

Promina has further insight: “I think for a lot of illustrators, we think about how we want to tell that specific tale and what we want to showcase in it. So then you start drawing it out, and it gets reviewed. Sometimes things don’t work out, and they ask you to change things, so then you revise it, which is quite rare!” She adds that, “for me personally, it is about how I engage kids to look at the pictures. In this particular book, I used a lot of things that I hid in the background. Kids have to actually look to find things in the book as well. For me, it was like I am telling a story. Sort of my childhood with an imagination.”

After Revisions

Nevertheless, some revisions are inevitable in publishing, both on the written and illustrated fronts. This means that the process very much continues after. For Nicolas, it involved inking the pages, sharing them again for notes, then scanning and digitally adding greyscale shading, since his graphic novel was in black and white. Then he “added text digitally, for future possible translations. These finished pages were sent to the editor as final deliverables.”

Picture books also undergo multiple revisions, particularly the cover. Monique points out that “a cover design can take a bit of extra time to finesse. Particularly because a few things need to feel right before a cover is approved, like the focus, messaging, type, composition, and colors. And like any book, there are a few “cooks in the kitchen,” who need to sign off on the cover as well.” Because of all this, I was surprised to learn, picture book cover design “can take anywhere from 3-8 rounds to call it final.”

Parting Words

It’s time to close the book on this topic, so to speak. But I hope this introduction to the world of illustration was at least partly as fascinating to you as it was to me, and that you’ll look at the illustrations in your books, children’s or not, with a little extra attention from now on. Perhaps, like Promina, the illustrator left some hidden treasures for you to find.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·